New Food Insecurity Data Highlight Minnesota’s Continuing Disparities and the Need for Multi-Sector Solutions

In recent months, food insecurity has received increased attention with rising unemployment from the COVID-19 pandemic and the changing food landscape in Minneapolis after the uprisings following the killing of George Floyd. Food insecurity – or not having adequate food because of lack of money or other resources – is not a new issue in Minnesota and affects people across the state. However, new U.S. Census data show BIPOC Minnesotans have been disproportionately impacted since the pandemic began.

Not all Minnesotans are impacted equally.

Since the beginning of COVID-19, many more Minnesotans have faced financial insecurity, bringing growing concerns about how to put food on the table or make food budgets last throughout the month. For some, food insecurity has been a new experience. For others, the pandemic has only added to high levels of stress, uncertainty, and financial insecurity they were already facing.

Minnesota Compass has been analyzing data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Pulse survey, which the Bureau began in April to understand the impact of COVID-19.

Rates of food insecurity have varied week to week, but, by July 21, 37% of Minnesotans reported some level of food insecurity. [1] Not all Minnesotans are impacted equally though. Black and Hispanic/Latino Minnesotans reported food insecurity at more than double the rate of White residents (83% of Black residents and 70% of Hispanic residents, compared to 32% of White residents). Fifty-two percent of Asian residents and 55% of people of other races, including American Indians, also reported some degree of food insecurity.

These disparities are alarming, but unfortunately are not new for Minnesota. Instead, they reflect the continuing impacts of policies and practices that over generations, have built barriers to economic security for BIPOC communities in Minnesota.

Disparities in food security predate COVID.

Even before COVID, Minnesota showed significant disparities in who struggled to have enough to eat. Black and American Indian Minnesotans were six times as likely to be enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) as White residents, and Hispanic/Latino and Asian residents were about three times as likely to be enrolled in the program.

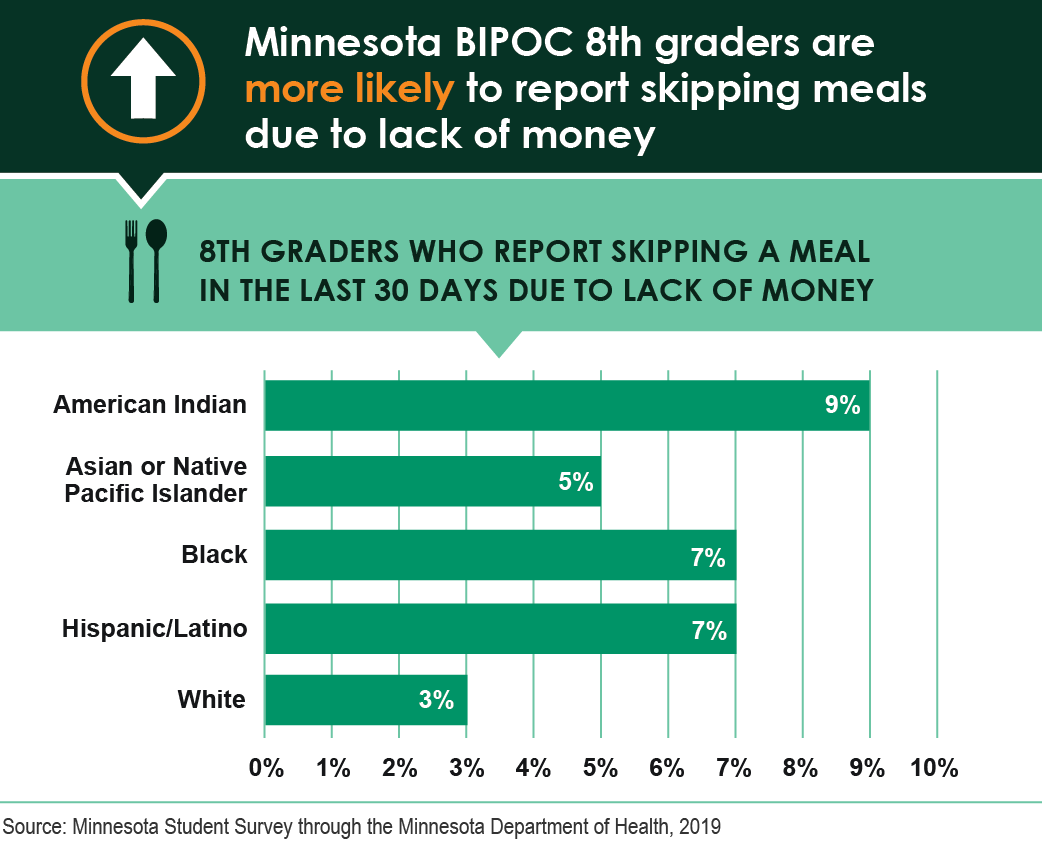

In 2019, American Indian 8th graders were three times as likely as White students to report skipping meals in the last 30 days due to lack of money, and Black and Hispanic/Latino 8th graders were twice as likely to do so.

Being able to get adequate food is influenced by a variety of factors. These include the availability of food in a community (e.g., the number of grocery stores, farmers markets, or food shelves in an area, as well as what food is available there), the cost of the food, whether individuals can afford it on their current incomes, and how easy it is to get to by available transportation. These, in turn, are influenced by local and national policies related to the economy, social safety nets, agriculture, transportation, and zoning.

While accessibility does matter, the main driver of food insecurity in the United States is lack of money to obtain food. In the most recent Pulse survey, of those reporting food insecurity, the main cause was not being able to afford food (40%). (Stores not having desired food (33%), and fear of going to the store (24%) were also reported as significant causes.) Research has also shown that we have enough food to feed everyone on the planet, so hunger is not caused by scarcity of food, but by inequality and poverty.

When we see inequitable outcomes, we must look at the ecosystem underlying it.

We must look at the underlying infrastructure that has made it easier for White residents to have enough money to put food on the table, and more difficult for BIPOC residents. The long-lasting impacts of racism and discriminatory policies that disadvantage BIPOC communities have led to differences in opportunities for education, employment, homeownership, and wealth generation. For example:

- Racial covenants in the first half of the 20th century, preventing non-White Minnesotans from purchasing homes in specific neighborhoods, significantly limited homeownership and wealth creation for Minnesotans of color. These policies also concentrated residents of color into specific neighborhoods, promoting further disinvestment.

- Policies such as the GI Bill and several New Deal programs created new economic opportunities for White Americans that were not fully available to communities of color.

- Welfare reform policies in the 1990s placed new immigration restrictions on who was eligible for SNAP, and undocumented immigrants have always been excluded from the program.

Today we continue to see impacts of these policies. As of 2018, the average household income for White residents was $71,400 compared to $48,000 for residents of color. Likewise, 20% of Minnesotans of color lived below the poverty line, compared with 7% of White Americans. This can have a critical impact on a family's ability to put food on the table. There is also evidence that some of these disparities may be widening during COVID, with Black workers disproportionately impacted by job losses since the beginning of the pandemic.

Where do we go from here?

The COVID-19 pandemic and our nation’s current reckoning with racial injustice have brought new attention to long-standing disparities and the health impacts of unjust systems. The economic downturn caused by the pandemic has both deepened inequities in food access and increased demand on food shelves and other safety net programs with more Minnesotans of all races and ethnicities experiencing food insecurity.

We need action on multiple levels to meet the immediate needs of residents, as well as to change policies, practices, and systems that have contributed to disparities in food insecurity.

Emergency food programs and other local organizations help meet immediate needs.

In the short term, we have seen increased investment from funders and government agencies to address immediate needs. For example, Hunger Solutions Minnesota recently partnered with the Minnesota Department of Human Services and the St. Paul and Minnesota Foundations to distribute funding to food shelves and other hunger relief organizations. The federal government has given states added flexibility in distributing SNAP benefits, and Minnesota implemented changes including one-time payments to families of students who qualify for free or reduced school meals, allowing SNAP to be used for online grocery purchases, providing the maximum benefits to all users, and waiving work requirements. The generosity of individuals donating money, food, or basic goods to organizations that are finding creative ways to meet the growing demand is also a critical source of support, but that will not be enough.

Longer-term solutions need to address the economic inequities that disproportionately impact communities of color.

Policies that make it easier for families to be financially secure, such as Minneapolis’s minimum wage ordinance and St. Paul’s guaranteed income pilot, may be promising first steps. Minnesota also has a long history of public and private entities building power to make healthy food available to all residents. See below for some examples of local efforts.

- Integrating food access and equity language in city comprehensive plans: A number of Minnesota cities are integrating language to improve food access in their comprehensive plans. Learn about how the process used by the cities of Duluth, Burnsville, Eagan, Lakeville, and Apple Valley.

- The evolution of the Northside Fresh Coalition: Learn about the work of this coalition, housed at Appetite for Change, improving food systems in North Minneapolis.

- Market Bucks: Explore the impacts of a program funded through the Minnesota Legislature to increase SNAP users’ purchasing power at farmers markets, providing matching funds of up to $10 per visit.

Ensuring that all Minnesotans have enough to eat is both a simple and complex problem. In a country that produces enough food to feed all of its residents, it is on us to look closely at the ecosystems that prevent some from accessing it, and the changes needed to ensure that none of our neighbors go hungry.

[1] Minnesota Compass categorized people as being food insecure if they answered that, in the last seven days, they sometimes or often did not have enough to eat or had enough to eat, but not the kinds of foods desired OR if they reported that they had slight or no confidence that they would be able to afford food in the next month.

However, recent food shortages at grocery stores may have prompted more people to report not being able to get the types of food they wanted. The percentages included here may overestimate the actual extent to which people are struggling to meet their food needs.

Amanda Hane was a Research Scientist at Wilder Research.

Photo by Joel Muniz on Unsplash.